A Novice Birder’s Guide to Prophecy

Join us for an in-depth conversation with Guest Curator Avery Geboers of the current A Novice Birder’s Guide to Prophecy exhibition along with Richard Pope, author of Flight from Grace – A Cultural History of Humans and Birds.

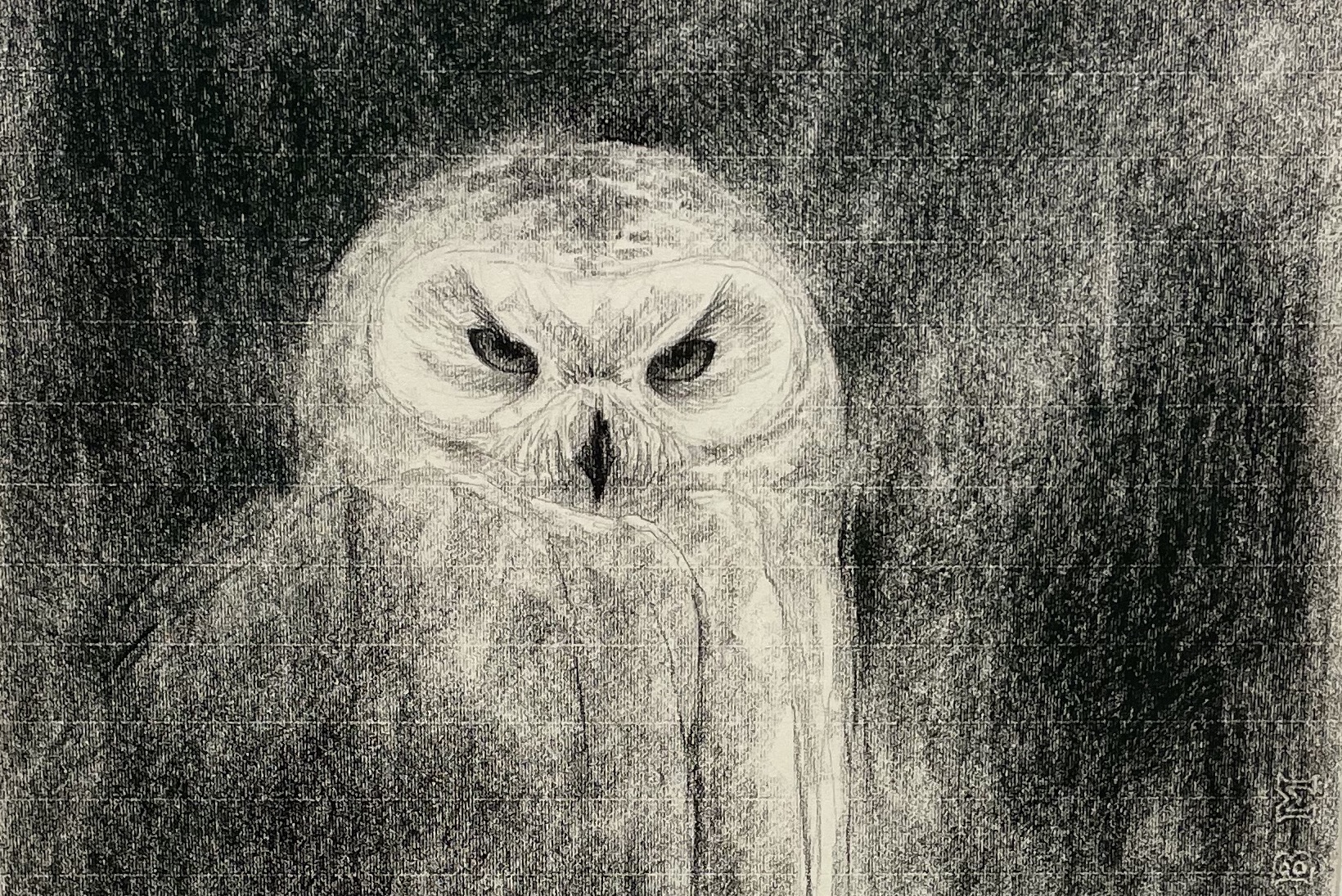

A Novice Birders’ Guide to Prophecy | Selections from the Permanent Collection

Many animals hold some sort of symbolic or mythic value, but birds hold tightly to their role as oracles and communicators from the other side. Perhaps it is there migratory nature, shifting from one hemisphere to another or their freedom to move from land to air (and sometimes water.) Whenever the reason, birds have long been used as a way for humans to attempt to see into the future and connect to the other side.

Ornithomancy derived from the Ancient Greeks, is the study of the flight patterns of birds to predict omens, they also had the practice of alectryomancy, which was solely devoted to divination through the pecking patterns of roosters. Similarly, the Romans practiced augury, expanding from observing flight or pecking patterns to analysing the broader behaviours of birds. While these practices have fallen out of popularity in the current day, people are still captivated by birds. We watch them in our backyards, wait for the return of robins in early Spring and look for ‘V’ formations of geese in Autumn skies. Birds still carry myths of premonition and otherworldly connections. While they might not have the same level of authority as they once did, their influence still permeates into our idioms and superstitions; seeing a red cardinal is thought to be a sign or message from a loved one that has passed away and should a bird be caught up indoors one must free it without any harm or ill consequences will follow. If that bird does not make it inside and rather flies into your window, a change is coming your way. It is commonly said that being defecated on by a bird is a sign of good luck –although some could argue this sentiment is less about fortune and more about trying to comfort the unwitting recipient.

“A Novice Birders’ Guide to Prophecy” showcases 11 works from the Art Gallery of Northumberland’s Permanent Collection centered around the theme of birds. This exhibition is inspired by their symbolism and myths as well as the roles they have played in how humans have conceptualized the world around them.

Attempting to form meaning from a work of art might seem to differ in ways from extracting your fortune from a flock of birds. But I believe that one can intermix the practice of reading the visual techniques and mediums employed by an artist with their own individual understanding of the species of birds depicted to create a new avenue of understanding, new symbolisms, and new myths. Because what is art, if not a moment to look deeper? A means of reflecting on our relationship with both what is separate from or deeply intertwined with our sense of self? This notion on the value of art to building ones’ own self-conception is at the foundation of nearly every piece of art created. But, to further understand how the specific works presented can be used in that capacity, it is necessary to delve into the ways in which humans have related themselves to birds in both the past and the present.

We cannot deny that humans are incredibly fascinated by birds. Birdwatching as a hobby has steadily grown in popularity. It has shifted from a means of research for scientists or status symbol for wealthy collectors in the 19th century, to a calming pastime for soldiers during the Second World War[1]. Now we see its growth as a response to increased urbanization and more specifically in the past two years, a response to social isolation and disconnection. Birdwatching became a fast-growing hobby among the Covid-19 Pandemic, commonly noted as being since that it was easily accessible to new birders, while also allowing them to feel more connected to nature and their environments.

In her essay “Chicken Auguries,” author Susan M. Squier describes augury as a “type of knowledge-making”[2] and connects it not only to our relationship with the divine or unknown, but to the animal and natural world itself. She adapts the term to refer to the relationship between bird and human that is formed by the practice of intimate observation. In addition, she speaks to how the fall of the practice of augury points to a larger disconnect from our natural intuition and with the birds and animals we exist with, stating that “augury stands as a metaphor for the modes of awareness, the knowledge-making practices that are being lost to human beings as we move into what is increasingly an instrumental relation to animals.”[3] She speaks in the context of agriculture rather than of prophecy, however whether it be through divination, farming, or birdwatching, the human-to-animal bonds created have the power to dismantle individualism and allow us to place ourselves into a wider, more unified and empathetic understanding of the world.

The building of a connection to something other is in and of itself a step toward deepening ones’ own sense of spirituality. And it is a connection many would argue is in dire need. Not only can it begin to mend the wear and tear created from a great period of seclusion, but is also beginning to be understood as a step in a larger collective rebuilding of the relationships we hold to our environment and natural world. In the preface of his recent book “Flight from Grace; A Cultural History of Humans and Birds” Richard Pope illuminates the grim intersection that we sit at between ecological and spiritual loss, stating that “birds and our treatment of them serve as an overarching metaphor for the betrayal of trust and duty that has led to the degradation of nature that we face today. Birds are the canary in the coal mine and are offering us an urgent warning.” (Pg xii)

Guest Curator: Avery Geboers

[1] Birkhead, Tim. “How Bird Collecting Evolved Into Bird-Watching.” Smithsonian Magazine, 8 Aug. 2022,

www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-bird-collecting-evolved-into-bird-watching-180980506/.

[2] Squier, Susan Merrill. “Chicken Auguries.” Configurations (Baltimore, Md.) 14.1 (2006): 69–86. Web.

[3] Squier, Susan Merrill. “Chicken Auguries.” Configurations (Baltimore, Md.) 14.1 (2006): pg 80. Web.